Yolanda Lopez: The Chicana Artist You Don’t Know About

November 17, 2021

Known for celebrating Latin women in her work, Yolanda Lopez was one of the most prominent artists to have come from the Chicano movement.

Lopez grew up in San Diego and was raised by her mother, who worked as a seamstress for the Navy base in San Diego, and her grandparents in a secular household. After graduating high school Lopez moved to San Francisco, where she experienced a political as well as artistic awakening. She joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the principal organizing groups of the civil rights movement. It was from this point on that she saw art and activism as intertwined, using her paintings and other works to empower the Latino community.

Her most notable work is Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe from her groundbreaking Virgin of Guadalupe series. This series sought to investigate the Virgin of Guadalupe as an influential female icon, with Lopez wanting to divest the Virgin of Guadalupe of her colonialist and patriarchal origins and transform her into an image of radical feminist optimism. In the painting Lopez depicts herself as the Guadalupe, showing off her muscular legs in her long strides. It is with this long leap in her painting that Lopez demonstrates that Chicanas are free from the oppressive social stigmas that limit women’s form of expression. According to the San Diego museum, this self-portrait is “one of the most iconic artworks to emerge from the Chicano Movement, and one of the era’s most widely reproduced images.”

Jill Dawsey, who curated an exhibition of Ms. López’s work that is scheduled to open in October at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego says, “Her priority was always her politics and ethical commitments. She never catered to the institutional art world, which has notoriously neglected Chicano artists.”

Jill Dawsey, who curated an exhibition of Ms. López’s work that is scheduled to open in October at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego says, “Her priority was always her politics and ethical commitments. She never catered to the institutional art world, which has notoriously neglected Chicano artists.”

Lopez’s Guadalupe series also consists of paintings dedicated to her mother and grandmother, using them to comment on the Chicana identity in American society. When asked about why she chose to transform this religious image Lopez said, “Because I feel living, breathing women also deserve the respect and love lavished on Guadalupe…”

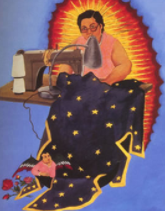

In her Margaret F. Stewart: Our Lady of Guadalupe piece, Lopez depicts her mother hard at work at her seamstress job. Her goal for the piece was to propose a new type of beauty, one that is atypical to the traditional slender figure, white, young, and glamorous beauty, but rather a fuller older woman hard at work. In her Guadalupe: Victoria F. Franco piece, Lopez pays homage to her grandmother, illustrating her as a sad but strong old woman who has skinned a serpent. About the piece, Lopez states “She is holding the knife herself, because she’s no longer struggling with life and sexuality. She has her own power.”

Lopez has said that she knew that she “was on to something,” with her series when she began to encounter resistance to her work. A printer refused to photograph the painting, saying that “you can mess around with my woman, my car, anything. But you don’t touch my lady,” referring to the Virgin. She also claims that a Mexican magazine that published the works reportedly received bomb threats.

According to Lopez, the goal of her series was to have the Latino community consider the new types of role models Chicanas needed and not simply adopt anything just because it is Mexican. With her paintings she wanted to pay homage to all kinds of women: working class women, old women, middle-aged overweight women, young, and self assertive women. Lopez once told the Salt Lake Tribune in 1995, “There were no public images of Mexican Americans or Latinos in mainstream culture that represented us in the broad scope of our humanity…What existed primarily were sleeping Mexicans, Spanish señoritas, bandito images … . Nothing at all that reflected that we had families, children, were working people, were creative or engaged in day-to-day activities.”

Lopez’s work was not only beautiful, but important as it admired and paid respect to communities and identities that were neglected by society and mainstream art. When reflecting on her life and work before her death, Lopez told the Tribune that she found meaning in paying “honor to the ordinary.”

“I am not as interested in the extraordinary,” she said. So, maybe we should try to find more beauty in the ordinary because who knows what good can come from it.